MOVIE OF THE MONTH

JAN ‘26

MOVIE OF THE MONTH

JAN ‘26

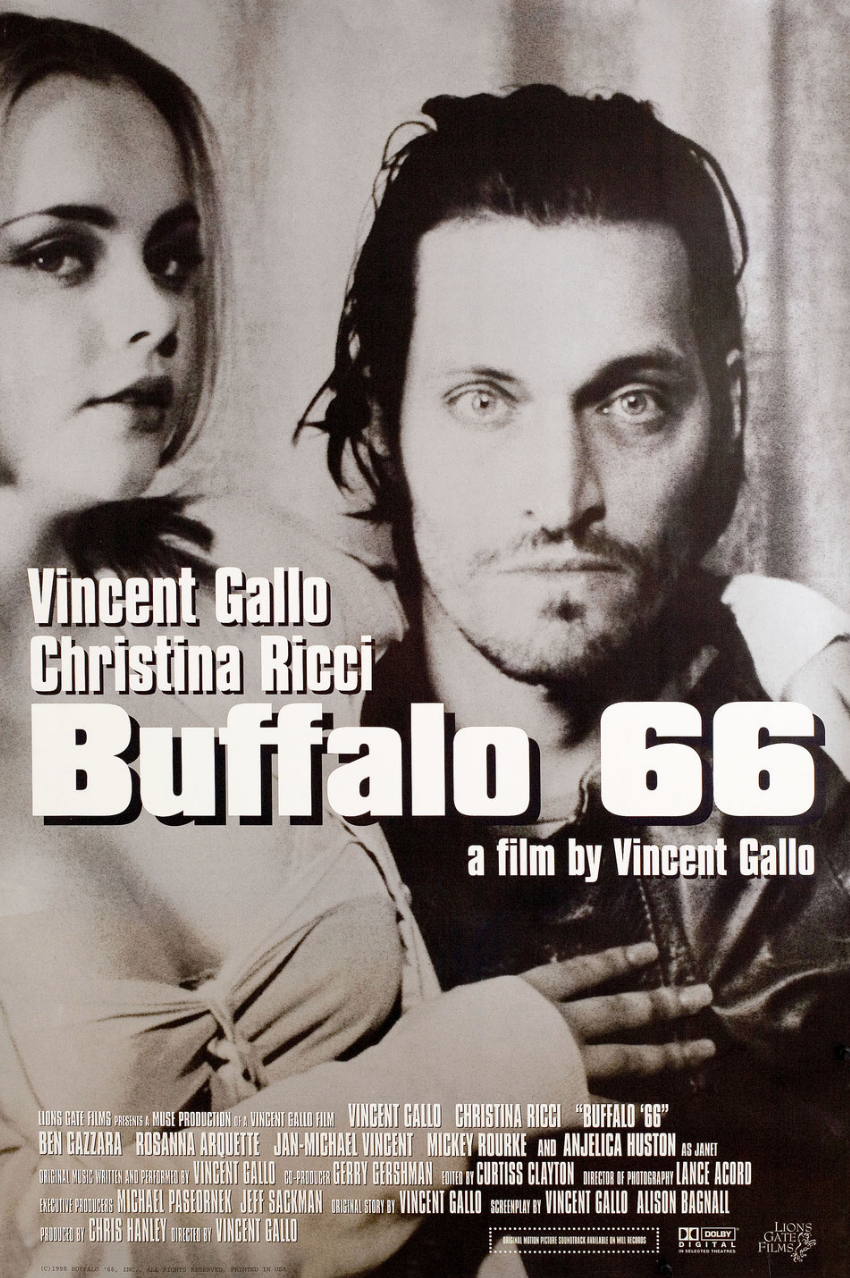

BUFFALO ‘66

Directed by Vincent Gallo | 1998 | 110 min

“that’s very nice. A HEART COOKIE.

WHO THOUGHT OF THE HEART?”

“I don’t know. somebody

ROMANTIC.”

It's impossible to discuss Buffalo ‘66 without addressing the filmmaker behind it, Vincent Gallo. The same could–and should, if the filmmaker did their job correctly–be said of any picture, but this holds particularly true for Gallo’s feature directorial debut. When it comes to reviews of the movie, critics and audiences alike tend to treat the film’s quality like something that happened in spite of Gallo rather than as a result of him. They approach the movie as if it were a cosmic fluke; as if Gallo was briefly granted a moment of competence by the gods who float over Hollywood’s skies. And with a simple wave of his hands, Buffalo ‘66 miraculously appeared from the ether. In 2026 we have a word for this kind of thought. It’s called cope.

There’s no denying that Buffalo ‘66 is a messy movie. The film’s production was loaded with inappropriate behavior and controversy. The film itself is just as full of indie experimentation and the ego of a young artist desperate to express themself. The strongly-opinionated politics of present-day Gallo further muddies things and makes it difficult for most viewers to come to terms with the fact that “someone who I don’t like made a movie that I do like.” But the reality is, the messiness that defines the movie is exactly what makes it so special. There’s so much of Gallo’s DNA in the film that when we watch it, he’s practically bleeding out onto the screen. A less wild, more predictable mind would never be able to make a movie like this. And anyone other than Vincent Gallo would never have been able to make Buffalo ‘66.

The reason that film nerds, myself included, find themselves so attracted to the movie is that from its chaos emerges a certain human beauty. It’s the story of a man whose life is without meaning and goes on to discover it through taking responsibility for his own actions. At the outset of the film, Billy Brown (Vincent Gallo) has just been released from prison. He’s served five years without his parents having any clue as to where he’s been and the first thing he plans to do as a free man is pay them a visit. To sell the success story he is going to tell them, he abducts a young tap dancer named Layla (Christina Ricci) and threatens her into playing the role of his wife, “Wendy.” Together they join Billy’s neglectful parents for dinner and by the credits, the two have come to develop feelings for one another.

What’s that you say? That’s repulsive! How can such a relationship be justified? Billy’s choice to abduct Layla is reprehensible! Yes. You’re right. It is. But to say that the movie is about Billy kidnapping a young girl is to say that Midnight Cowboy is about a guy who wants to get laid while really, it’s the story of every person with a dream of making it in a new place. Or to say that The Godfather is a story about disposing of every mortal enemy rather than about familial obligation and the repeated sins of fathers and sons. But when a filmmaker is caught in the crossfire of public disapproval, whether deservingly so or not, their work suddenly becomes a means to further condemn them. Regularly observant critics cover their eyes and ears, screaming like preschoolers to drown out their understanding of the film. Media literacy vanishes at the first sign of controversial authorship so that consciences can be comfortably assuaged. It’s simply too disturbing for them to recall that the actions of a fictitious character don’t carry the same weight as that of a person in the real world. Audiences jump to welcome Darth Vader back to “the good side” at the end of Return of the Jedi, but I get the sense they would be considerably less excited to do so with any real-life despot. Should Billy’s actions be repeated by a living, breathing person, they certainly wouldn’t be answered with such a tender romance. But within the realm of film, where actions are only part literal and part artistic metaphor, then sure, why not? Even so, I suspect that the movie’s real answer to Billy’s decision-making is more complex than it’s typically given credit for.

Gallo grew up in Buffalo, New York, where the film is set. And while the film isn’t autobiographical (which Gallo has gone on record saying), he’s obviously familiar with its liminal corners and frozen over strip-malls. And from those miserable, boring snow-covered streets of Buffalo, there is a magic happening. In her heavy blue eyeshadow and platinum hair, Layla becomes like an ice queen and the movie akin to a fairytale (after all Beauty and the Beast is too a variation on Stockholm Syndrome). In moments of dreamlike lucidity, Gallo further breaks from the otherwise real and lived-in world of Buffalo ‘66. In almost Lynchian scenes, Billy’s father (Ben Gazzara) performs a surreal cover of “Fools Rush In (Where Angels Fear to Tread)” and Layla tap dances under an impossible spotlight to “Moonchild” by King Crimson in a bowling alley. Across the film, similar uncanny moments unfold against the backdrop of licensed music. Billy visits the strip club of a former football pro who he misguidedly blames for all the disappointment in his life. In a full-on fantasy sequence, Billy assassinates him set against “Heart of the Sunrise” by Yes before rethinking things and walking out the strip club a changed man. Repeatedly, the moments that deviate most clearly from the “real world” of the film are defined by Gallo’s use of soundtrack.

Importantly, the film’s soundtrack returns one final time at the very end of the movie. Before returning home to Layla, Billy visits a coffee shop with infectious enthusiasm. He buys a cookie for a random customer, leaves extra money for the man behind the counter and walks around with a previously unseen charisma. He’s thrilled just to be getting a hot chocolate for his soon-to-be-girlfriend. Then, just as we’re riding this great emotional high with Billy, cue “Sweetness” by Yes. We’re ready for the fairytale ending and ‘66 hard cuts to the closing shot of Layla and Billy in bed together, him holding her in his arms. It can’t get much sweeter. Only, Layla isn’t smiling. In fact, she looks like she’d really rather be anywhere but there. And that sugary music — well, every time we’ve heard a licensed song previously in the film, it's been joined to a scene that wasn’t entirely real. So is this it then? Is this the ending or something else entirely?

On the subject of the film’s message, Gallo stated, “In Buffalo '66, the idea was of this extremely misguided victim who saw himself as a victim in the most unreasonable, unrealistic ways. That his life transforms the minute he takes responsibility for his own life is a direct political statement – a very uncomfortable one for many people because socialists feel quite opposed to that.” With Buffalo ‘66, Gallo is rejecting the idea that society is to blame for everyone’s predicament in life. We are creatures with agency over our own lives and we reap the outcome of our choices and actions. The situation of one’s existence, according to Gallo, is the result of their own behavior.

If this is true of Billy in the film — that his status at the end of the movie is the direct result of his previous choices — then shouldn’t the same hold true for Layla? While Billy is an ex-con and social outcast who’s thrilled to be getting a girlfriend, Layla is a young girl with the rest of her life ahead of her. And the decision to be with Billy, understandably, is one that she’s perhaps come to regret in the film’s final moment. Billy has gotten his fairytale ending, but in the end it's the same as all fairytales. It’s just a fantasy and the illusion doesn’t last forever.

- Matt

BUFFALO ‘66

Directed by Vincent Gallo 1998 | 110 min

“that’s very nice. A HEART COOKIE. WHO THOUGHT OF THE HEART?”

“I don’t know. somebody ROMANTIC.”

It's impossible to discuss Buffalo ‘66 without addressing the filmmaker behind it, Vincent Gallo. The same could–and should, if the filmmaker did their job correctly–be said of any picture, but this holds particularly true for Gallo’s feature directorial debut. When it comes to reviews of the movie, critics and audiences alike tend to treat the film’s quality like something that happened in spite of Gallo rather than as a result of him. They approach the movie as if it were a cosmic fluke; as if Gallo was briefly granted a moment of competence by the gods who float over Hollywood’s skies. And with a simple wave of his hands, Buffalo ‘66 miraculously appeared from the ether. In 2026 we have a word for this kind of thought. It’s called cope.

There’s no denying that Buffalo ‘66 is a messy movie. The film’s production was loaded with inappropriate behavior and controversy. The film itself is just as full of indie experimentation and the ego of a young artist desperate to express themself. The strongly-opinionated politics of present-day Gallo further muddies things and makes it difficult for most viewers to come to terms with the fact that “someone who I don’t like made a movie that I do like.” But the reality is, the messiness that defines the movie is exactly what makes it so special. There’s so much of Gallo’s DNA in the film that when we watch it, he’s practically bleeding out onto the screen. A less wild, more predictable mind would never be able to make a movie like this. And anyone other than Vincent Gallo would never have been able to make Buffalo ‘66.

The reason that film nerds, myself included, find themselves so attracted to the movie is that from its chaos emerges a certain human beauty. It’s the story of a man whose life is without meaning and goes on to discover it through taking responsibility for his own actions. At the outset of the film, Billy Brown (Vincent Gallo) has just been released from prison. He’s served five years without his parents having any clue as to where he’s been and the first thing he plans to do as a free man is pay them a visit. To sell the success story he is going to tell them, he abducts a young tap dancer named Layla (Christina Ricci) and threatens her into playing the role of his wife, “Wendy.” Together they join Billy’s neglectful parents for dinner and by the credits, the two have come to develop feelings for one another.

What’s that you say? That’s repulsive! How can such a relationship be justified? Billy’s choice to abduct Layla is reprehensible! Yes. You’re right. It is. But to say that the movie is about Billy kidnapping a young girl is to say that Midnight Cowboy is about a guy who wants to get laid while really, it’s the story of every person with a dream of making it in a new place. Or to say that The Godfather is a story about disposing of every mortal enemy rather than about familial obligation and the repeated sins of fathers and sons. But when a filmmaker is caught in the crossfire of public disapproval, whether deservingly so or not, their work suddenly becomes a means to further condemn them. Regularly observant critics cover their eyes and ears, screaming like preschoolers to drown out their understanding of the film. Media literacy vanishes at the first sign of controversial authorship so that consciences can be comfortably assuaged. It’s simply too disturbing for them to recall that the actions of a fictitious character don’t carry the same weight as that of a person in the real world. Audiences jump to welcome Darth Vader back to “the good side” at the end of Return of the Jedi, but I get the sense they would be considerably less excited to do so with any real-life despot. Should Billy’s actions be repeated by a living, breathing person, they certainly wouldn’t be answered with such a tender romance. But within the realm of film, where actions are only part literal and part artistic metaphor, then sure, why not? Even so, I suspect that the movie’s real answer to Billy’s decision-making is more complex than it’s typically given credit for.

Gallo grew up in Buffalo, New York, where the film is set. And while the film isn’t autobiographical (which Gallo has gone on record saying), he’s obviously familiar with its liminal corners and frozen over strip-malls. And from those miserable, boring snow-covered streets of Buffalo, there is a magic happening. In her heavy blue eyeshadow and platinum hair, Layla becomes like an ice queen and the movie akin to a fairytale (after all Beauty and the Beast is too a variation on Stockholm Syndrome). In moments of dreamlike lucidity, Gallo further breaks from the otherwise real and lived-in world of Buffalo ‘66. In almost Lynchian scenes, Billy’s father (Ben Gazzara) performs a surreal cover of “Fools Rush In (Where Angels Fear to Tread)” and Layla tap dances under an impossible spotlight to “Moonchild” by King Crimson in a bowling alley. Across the film, similar uncanny moments unfold against the backdrop of licensed music. Billy visits the strip club of a former football pro who he misguidedly blames for all the disappointment in his life. In a full-on fantasy sequence, Billy assassinates him set against “Heart of the Sunrise” by Yes before rethinking things and walking out the strip club a changed man. Repeatedly, the moments that deviate most clearly from the “real world” of the film are defined by Gallo’s use of soundtrack.

Importantly, the film’s soundtrack returns one final time at the very end of the movie. Before returning home to Layla, Billy visits a coffee shop with infectious enthusiasm. He buys a cookie for a random customer, leaves extra money for the man behind the counter and walks around with a previously unseen charisma. He’s thrilled just to be getting a hot chocolate for his soon-to-be-girlfriend. Then, just as we’re riding this great emotional high with Billy, cue “Sweetness” by Yes. We’re ready for the fairytale ending and ‘66 hard cuts to the closing shot of Layla and Billy in bed together, him holding her in his arms. It can’t get much sweeter. Only, Layla isn’t smiling. In fact, she looks like she’d really rather be anywhere but there. And that sugary music — well, every time we’ve heard a licensed song previously in the film, it's been joined to a scene that wasn’t entirely real. So is this it then? Is this the ending or something else entirely?

On the subject of the film’s message, Gallo stated, “In Buffalo '66, the idea was of this extremely misguided victim who saw himself as a victim in the most unreasonable, unrealistic ways. That his life transforms the minute he takes responsibility for his own life is a direct political statement – a very uncomfortable one for many people because socialists feel quite opposed to that.” With Buffalo ‘66, Gallo is rejecting the idea that society is to blame for everyone’s predicament in life. We are creatures with agency over our own lives and we reap the outcome of our choices and actions. The situation of one’s existence, according to Gallo, is the result of their own behavior.

If this is true of Billy in the film — that his status at the end of the movie is the direct result of his previous choices — then shouldn’t the same hold true for Layla? While Billy is an ex-con and social outcast who’s thrilled to be getting a girlfriend, Layla is a young girl with the rest of her life ahead of her. And the decision to be with Billy, understandably, is one that she’s perhaps come to regret in the film’s final moment. Billy has gotten his fairytale ending, but in the end it's the same as all fairytales. It’s just a fantasy and the illusion doesn’t last forever.

- Matt